Microservice Communication over RPC?!

Intro

If you’ve been in the industry long enough, you’ve probably had your chance to say goodbye to good ol’ friend RPC. We’ve seen Java’s RMI become popular and virtually dissapear, we’ve witnessed SOAP (not exactly RPC, but similar) to fall out of favor. I won’t even mention CORBA. Surely these paradigms, technologies, protocols, and implementations are not all exactly pure RPC representatives. However, they do have one thing in common: they allow distributed systems to communicate with each other by sending messages, and that, my friend, is a basis of RPC.

RPC has been criticised a lot, and industry by far and large has moved on. REST and message driven architectures took over. However, if we learn from mistakes made by some RPC implementations, mix in some AMQP goodness, JSON flexibility and convenience, we might get a pretty decent solution - RPC over AMQP. A library that provides this, and more is called Nameko. Nameko has other features apart from RPC, but we focus on this part for the rest of this post.

AMQP

Before we dive into how Nameko works we need to understand what AMQP is. Let’s have a quick look.

The Advanced Message Queuing Protocol (AMQP) is an open standard application layer protocol for message-oriented middleware. The defining features of AMQP are message orientation, queuing, routing (including point-to-point and publish-and-subscribe), reliability and security. Wikipedia

RabbitMQ is a very decent message broker that implements AMQP among other protocols.

This tutorial from RabbitMQ’s website describes how one can implement RPC via AMQP 0-9-1 protocol. The workflow I describe here, which is used by Nameko, is exactly based on the same idea described in the tutorial. However, this tutorial mentions and doesn’t solve the problem of exceptions during processing, timeouts, server unavailability, etc. This is where Nameko comes handy.

Nameko

Nameko is:

A microservices framework for Python that lets service developers concentrate on application logic and encourages testability.

Nameko extends RPC implementation idea from the tutorial mentioned above and adds a few key features to make development of RPC services easy. I’m not going to cover stack accumulation behavior in this post. Which is essentially tracing the lineage of RPC calls, which might be useful, but not essential for RPC to work.

Other than that, I should mention that client payload is sent as JSON which looks like this: {"args": ["first argument"], "kawrgs": {}}. Message envelope contains: routingKey=hello_service.test endpoint value. Response from server looks like this: { "result": "hello world from server", "error": null }. In case server got an exception, the exception class is sent together with the error message to the client. Client will raise this exception to simulate local error. More details on it in a separate article or as code.

What if you decide to write a microservice in something other than Python? You can check if there are existing implementations in your language of choice. Chances are you’d have to implement it yourself. No biggie, that’s why I’m writing this article afterall. You can read up on additional discussion here where I was trying to understand how Nameko works and getting help from contributors.

There are 2 ways to call RPC methods according to Nameko docs: blocking and async:

Normal RPC calls block until the remote method completes, but proxies also have an asynchronous calling mode to background or parallelize RPC calls:

with ClusterRpcProxy(config) as cluster_rpc:

hello_res = cluster_rpc.service_x.remote_method.call_async("hello")

world_res = cluster_rpc.service_x.remote_method.call_async("world")

# do work while waiting

hello_res.result() # "hello-x-y"

world_res.result() # "world-x-y"This is not too bad since you don’t block immediately, but you still have no idea when result will be ready. You are not immune from blocking with this approach either. You could poke into RpcReply object returned from call_async, especially resp_body, but I’d rather not.

Consider using Events/Pub-Sub feature for trully asynchronous behavior if you are terrified of blocking.

Nameko RPC implementation in your language of choice doesn’t have to be blocking though. In Scala I use Future or Akka Actor to get async result instead.

RPC Implementation

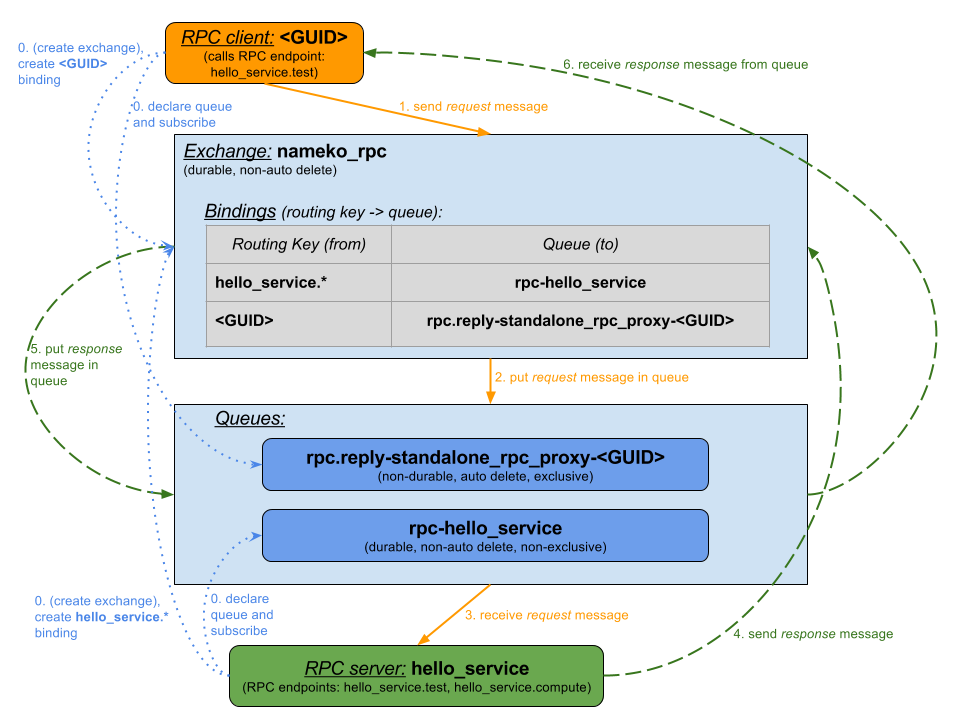

For our example let’s assume that we have an RPC server named hello_service, it implements two RPC methods: test and compute. Our client will be calling hello_service.test RPC endpoint.

RPC implementation over AMQP is essentialy a two way pub-sub communication. Here are the steps taken as described in the diagram below:

- Initial setup is being done. An exchange named

nameko_rpc, which is durable and non-auto delete is created by a client/server. All bindings, which define routing of messages to queues based on routing keys, will go into that exchange. A server creates a queue named after itself:rpc-hello_service. Server binds this queue to a routing keyhello_service.*. Thus, all messages sent with this routing key will go to the server’s queue. A client does a similar setup by picking any unique ID on startup -<GUID>, creating it’s own non-durable, auto delete, exclusive queue, and binding<GUID>routing key to that queue. That’s how it will receive RPC responses from server. Both client and server, obviously, subscribe to receive messages on their corresponding queues. Now everything is ready for messages to be sent. - Client sends a message with routing key

hello_service.testand a propertyreply_to=<GUID>to thenameko_rpcexchange. The message also containscorrelation_idproperty for traceability and mapping of requests to responses. - Exchange looks up the binding for the routing key, which matches the wildcard based key:

hello_service.*and places the message intorpc-hello_servicequeue. - RPC server, having subscribed to its

rpc-hello_servicequeue, receives the message. - RPC server does some processing and sends a response message to … surprise, surprise,

nameko_rpcexchange. The message is sent with routing key<GUID>and the samecorrelation_idis copied back for the client to know which request this response belongs to. - Similarly to #2, the exchange routes the message, this time, to client’s queue

rpc.reply-standalone_rpc_proxy-<GUID>. - RPC client receives response since it subscribed to it’s queue.

Note the importance of the fact that the client picks a new <GUID> every time on startup to uniquely represent it’s queue. This way you can have multiple clients of the same type/codebase acting in complete isolation.

Correlation ID is important, as I mentioned earlier, to know which response belongs to which request. Because of asynchronous nature of this RPC implementation, you might receive responses out of order. There is no other way to know the mapping, other than using some ID.

This RPC architecture has many nice properties, and a few concerns. Let’s check them out.

Advantages:

- Scalable - you can add/remove clients and servers easily to scale your load. One message will be processed only by one server.

- Decoupled - messages are serialized as JSON and can be processed by any language you wish to write your server in. In my project I replaced one slow microservice written in Python with analogous one written in Scala (~20 times faster). As long as you keep your

APIremote procedure interface compatible, i.e. don’t change parameters or function name, you can change server code without breaking the client. - Location Transparent - there is no service discovery required. You applications need to know how to connect to AMQP. The rest will be taken care of by the setup steps described above in #0.

- Reliable Delivery - MQ takes care of message delivery, so you don’t have to implement the retry logic (terms and conditions apply).

- Simplicity - fairly simple and straightforward to implement protocol. You don’t need to regenerate a lot of boilerplate in case of API changes.

Disadvantages:

- Latency - sending messages through a queue introduces another network hop which increases latency.

- Payload Size - usually limited payload size because a queue is not meant to store large BLOBs. A workaround involves storing payload somewhere else and referencing it in a message - requires additional work and makes things more complicated.

- Complexity - although, compared to other RPC protocols, AMQP/Nameko is simpler it’s still more complex than direct messaging between applications.

- Blocking - the way client implements RPC might be blocking. If the client waits for response in non-asynchronous manner, it might be doing busy waiting and wasting resources. Messaging and event driven architectures would be more efficient and scalable in such case.

Conclusion

RPC is not dead just yet! It can be convenient in many cases, and if you look at Nameko examples they are quite compelling due to their simplicity.

One of the criticisms to RPC was that developers might be ignorant of whether a function call is local or remote, which might lead to unpredictable behavior and complicated debugging. You do want to be aware of latency in RPC applications and make it explicit to developers.

Another criticism is that RPC is usually implemented in blocking manner to make all code look/feel the same. Blocking can be avoided with additional language constructs available in your language, but this will make your RPC code look different from normal code. Which I think is a good thing anyway.

If you are looking for more advanced distributed architecture, I’d recommend to check out Reactive Architecture: responsive, resilient, elastic, message driven.