NN From Scrach in Scala

Motivation

It’s been suggested by many that one of the best ways to learn about machine learning (ML) and neural networks (NN) is by implementing ML algorithms from scratch.

I took this idea as motivation to implement my own NN library. Furthermore, I was and still am curious to see how functional programming style fits with this kind of problem. Can we keep side effects to minimum while trying to achieve highly performant and clean code? Can we make programming of library features and later utilization of a NN library very safe and strict in terms of avoiding logical errors and pitfalls? While achiving this safety, can we manage to keep things flexible and convenient for the end-user? These are the topics I was very curious to explore further.

At the present moment many of these problems are not addressed yet in the code, but a good foundation is put in: each function involved in computation can be called pure from end-user perspective. Yes, there is some logging, but let’s ignore it for now.

Implementation

I implemented a basic NN using Scala (code) and breeze - a numerical processing library. I used data from Andrew Ng’s Coursera Deep Learning course which contains pictures of cats and other animals.

Numerical Library

Before I started I decided to pick a high performance linear algebra library. It would be fairly easy to write basic components like matrix, vector and activation functions myself without resorting to a library. However, it wouldn’t be as fast as an optimized implementation. JVM these days beats C/C++ in terms of speed in many scenarios because JIT can compile bytecode specifically for your processor architecture and also inline methods, unroll loops, eliminate dead code, etc. However, a big feature JVM doesn’t provide is direct access to hardware instructions, which is essential for utilizing vectorization such as SIMD. Vectorization takes advantage of modern CPU/GPU instructions by loading data in chunks and performing a single instruction on that chunk of data at once. This dramatically reduces time it takes to operate matrices, but takes carefull platform specific implementation in native language like C, Fortran, Assembly, etc. There is no point to try to reimplement highly optimized libraries like LAPACK and BLAS, especially for this kind of project.

Why does the speed matter for a toy project you might ask? When using Breeze even for a small dataset that I have, I noticed large difference in speed when using native implementation through JNI vs using reference implementation in Java. If you run many small experiments time adds up considerably and none of us likes to wait, right?!

When using native implementation one epoch completes within ~2 seconds, while using Java reference implementation it takes ~20 seconds. Before you compare these numbers, though, take into account that CPU consumption is around 330% for the former, and 100% for the later on my I7-6820HQ - 4 cores, 8 threads i7 CPU laptop. This means that reference Java implementation is not multithreaded. To make things fare I limited veclib (on my Macbook) to use only single thread by setting an environment variable: export VECLIB_MAXIMUM_THREADS=1. Now that we are comparing apples to apples we can see that native implementation executes in 3 seconds, while reference in 20 seconds. For more performance comparisons for underlying implementations see netlib-java.

I finally picked Breeze as a linear algebra library because it has nice Scala API and could use native implementation when available, falling back to reference Java implementation if JNI failed to load native libraries.

Correctness

It’s very easy to implement a ML algorithm incorrectly without knowing it. Regular applications might crash or give clearly wrong results which are easy to spot. ML applications might just not perform as well as they should if they have a small error. It’s also very hard to pinpoint that error given many numerical inputs and outputs. Numbers just don’t make much sense to us humans, we prefer categories and visual results.

Because of that I decided to implement every function with unit tests. I had a reference implementation in Python/Numpy from the course I completed, thus, I could get data for intermediate steps. I implemented some utility functions to help me do assertions in unit tests. For example, def matricesShouldBeEqual(actual: Mat, expected: Mat, thresh: Double = 1e-7d): Assertion takes two matrices and compares them for equality within allowed threshold. Some loss of precision is expected when dealing with floating point arithmetic, hence the threshold.

Packaging and Configuration

The code compiles into a JAR file that can be run by Java 8 runtime. There are a few configuration options that can be overriden via cmd args or config file. For example, you can run it like this:

java \

-Dapplication.nnMetaParams.layersDimensions='[20, 7, 5, 1]'

-Dapplication.nnMetaParams.iterations=1000 \

-Dapplication.nnMetaParams.learningRate=0.009 \

-Dapplication.trainParams.costReportIters=10 \

-Dapplication.trainParams.randSeed=1 \

-jar target/scala-2.12/scala-nn-assembly-0.1.jar

For more details see the repo’s README.

Plots

I’ve implemented a few plots to help with some visualizations. They can be run as executable classes (with main method) from within the JAR. Here is the list:

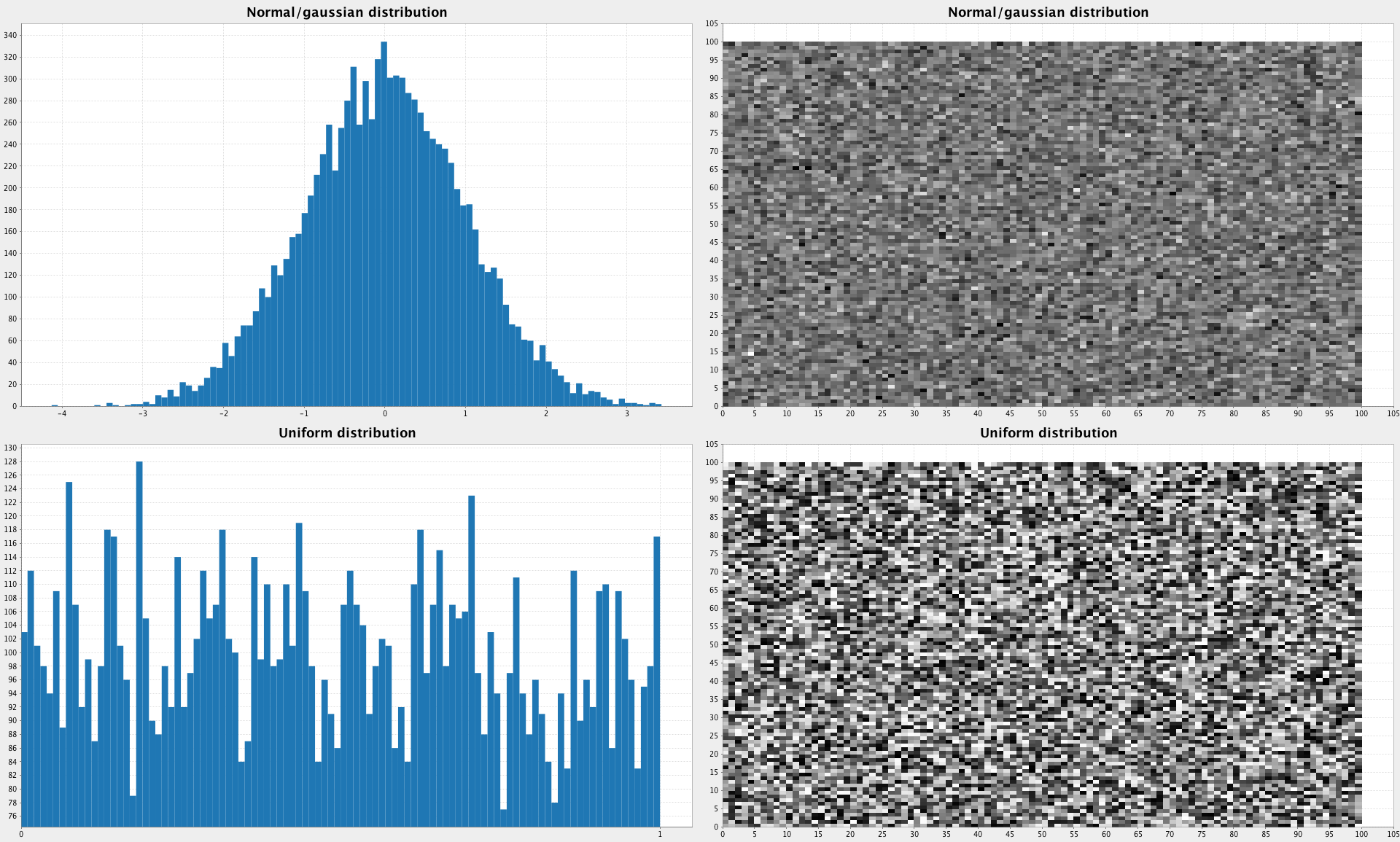

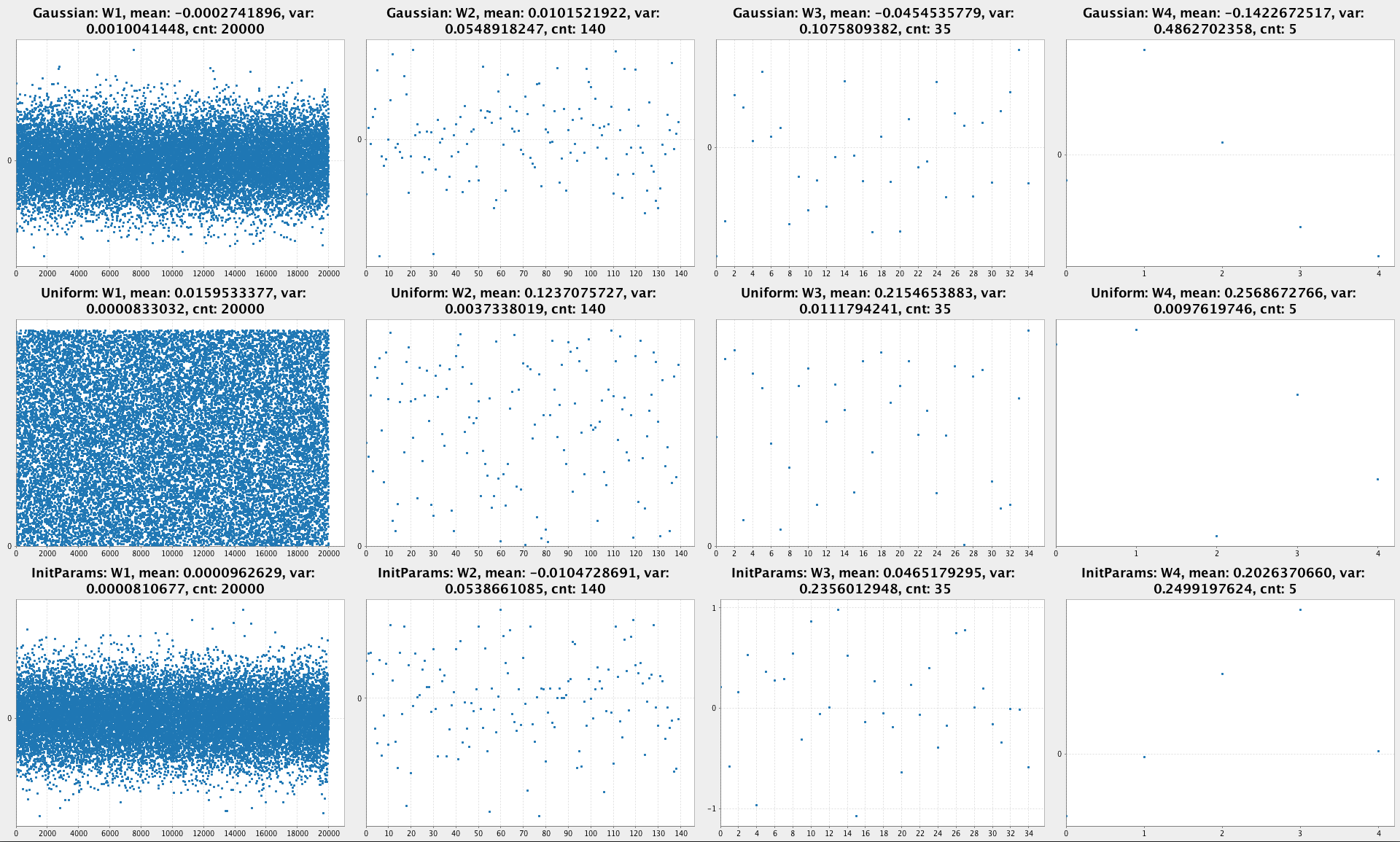

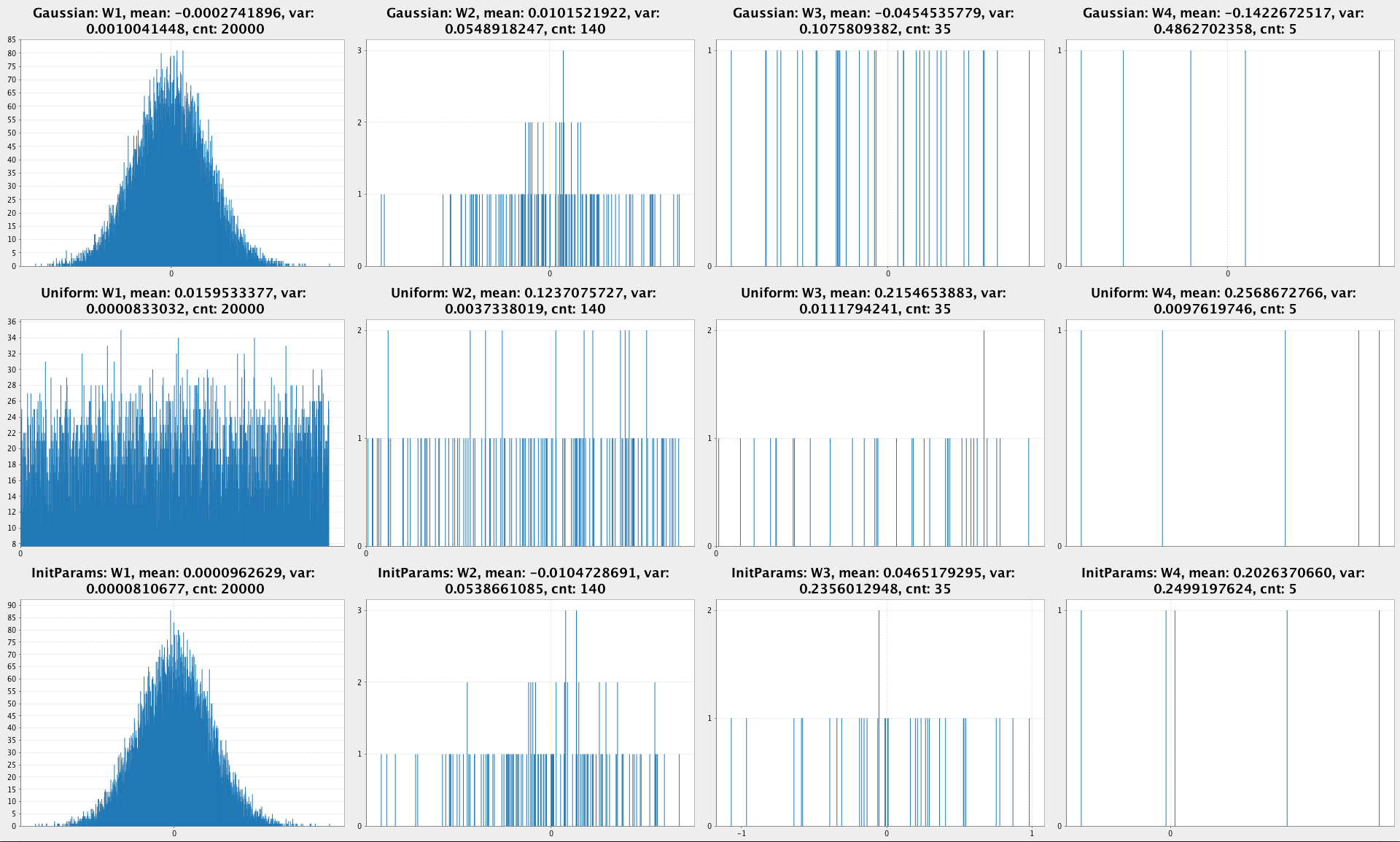

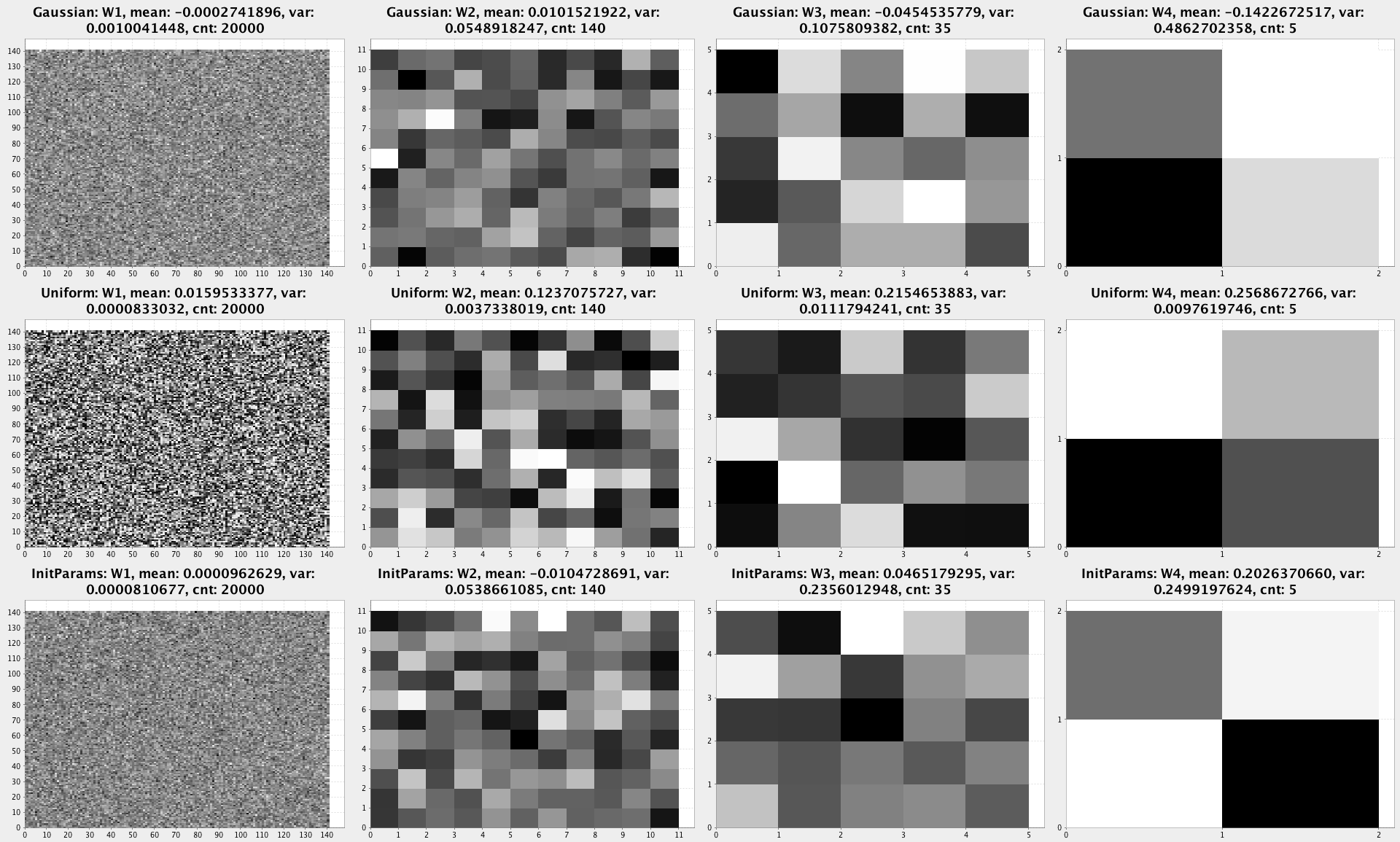

PlotDistributions- compares uniform random distribution with Gaussian by plotting both.PlotInputImages- helps you to visualize images from the dataset. The dataset in the repo is converted toCSVso it’s not easy to look at images otherwise.PlotUntrainedNN- plots randomly initialized weights of a NN.

See the Appendix for examples.

Learnings and Recomendations

There are many things you can learn, even my implementing a vanilla NN. I plan to add more features, so I learn about them better. Here is a list of some things I’ve learned or recommend to keep in mind when implementing your own NN:

- Initialization really matters. Randomly seeded weights will play important role in how well your NN will learn. It might get stuck in a local minima or have a very slow convergence if weights are not initialized properly. In the start I observed that my NN produced completely different accuracy in 60-80% range based on the same initialization method seeded from gaussian distribution, but started from different random seed. There is a ton of research on weight inititialization as it matters a lot when NN get large in size.

- Vectorization makes things much faster. Avoid loops and use native optimized libraries for best performance.

- Beware of numerical stability. Even if you implement NN correctly you might get numerical overflows if weights keep growing rapidly. There are ways to deal which involve some sort of weight regularization and weight constraints.

- Python has great ecosystem when it comes to ML. That’s why it’s so popular in this area. When it comes to other languages like Scala there are less resources available, and the libraries are less mature. Nonetheless, Scala is trying to catch up with Python and has good merits to do so. Apart from numerical computation, plotting is also underdeveloped.

- It’s a good idea to break down your ML algorithm into very small pieces (functions) whenever possible. You can test these pieces using standard aproaches like unit tests, and you can implement gradient check to test larger steps like forward/back propagation.

- Automatic differentiation or symbolic differentiation is the way to go for NN libraries. Computing gradients and keeping activations in cache is a good learning excersise but requires extra repetitive work and is prone to errors.

- Make sure your linear algebra library supports passing random seed to make results consistent for reproducable research and testing.

What’s Next

Whenever I find time I’ll try to enhance this library both in engineering terms like making it more type safe or flexible, as well as adding more NN features. I’m not expecting this to become a fully blown Tensorflow, but maybe it will reach the point where it makes sense to directly embed it into (JVM) ML projects which need simple NN without overhead of large libraries.

Appendix

These are the plots described above:

PlotDistributions:

PlotUntrainedNN - Initial NN weights as scatter plot:

PlotUntrainedNN - Initial NN weights as histogram:

PlotDistributions - Initial NN weights as an image:

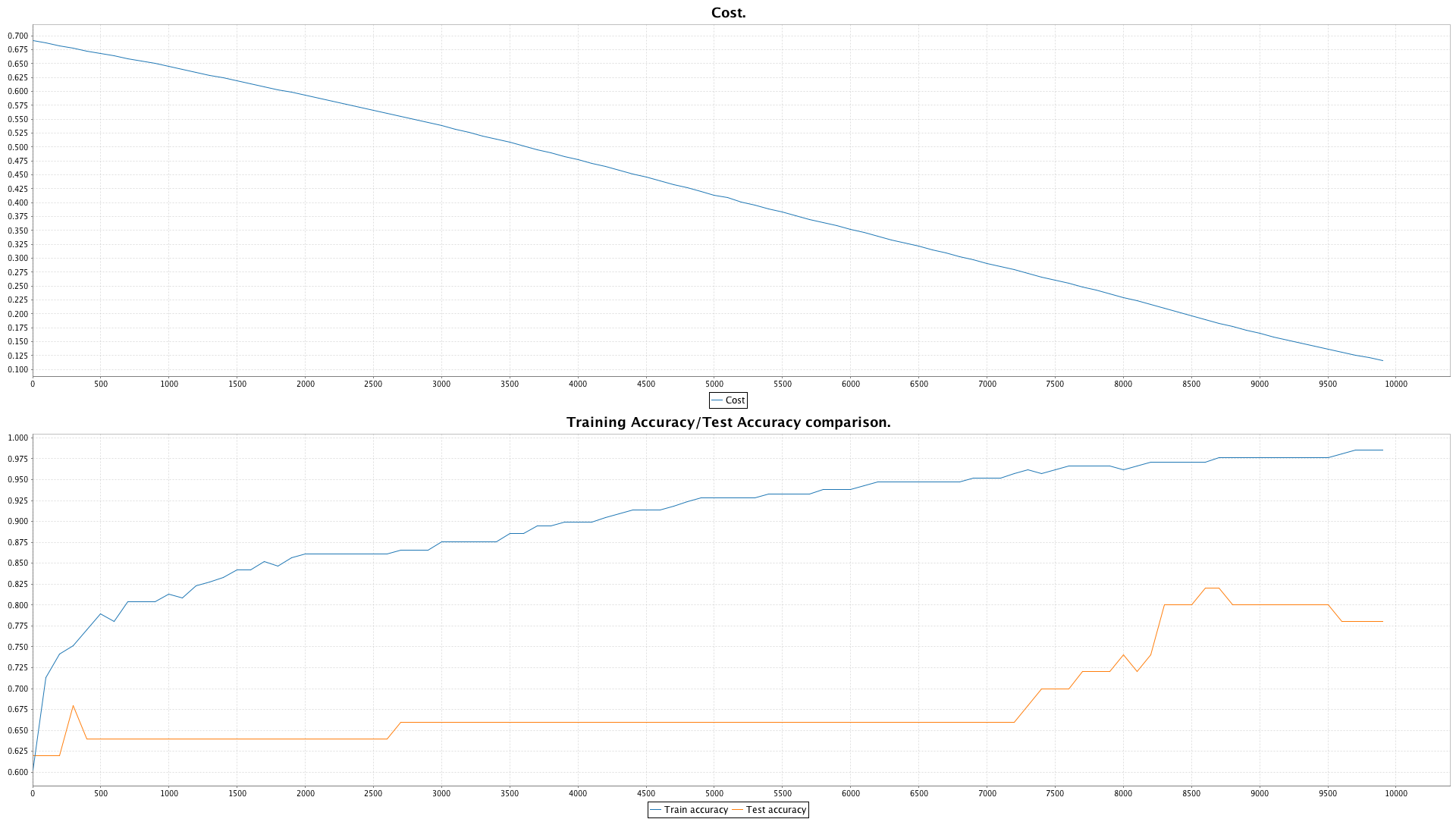

This is cost and accuracy plot representing full training cycle:

You might notice something very wrong in this plot: test accuracy is plotted for each iteration! This is a bit of a cheat and a no-no for productive usage. However, for debugging the way system works and for getting more insights on how training happens, and when we encounter overfitting through out training process I’ve added this feature. This cheat should never be used for training real NNs, estimate accuracy only once when training is done, or according to cross-validation procedure.